Please Follow us on Gab, Minds, Telegram, Rumble, Truth Social, Gettr, Twitter

On Saturday, January 4, 2025, less than two weeks after residents at Li’l Abner Mobile Home in Sweetwater, Miami-Dade whom your correspondent reported on in December filed a lawsuit against developer Raul F. Rodriguez to avoid eviction, The Miami Herald released a list which cast the eviction fight in a broader light. It showed the top sixteen donors to Democratic Miami-Dade Mayor Daniella Levine Cava and the majority-Democratic Miami-Dade County commissioners in 2024—really, a map linking real estate interests like Rodriguez’s to Democratic political dominance in Miami-Dade, whose citizens vote Republican.

Of the top sixteen donors, at least five are heavily invested in changing the face of the county through luxury buildings or “affordable housing,” and another has been a major real estate player for many years. Two more are Florida utility companies which benefit directly from this housing boom, since every new apartment needs power. Another, a Canadian entertainment conglomerate, will also benefit, since it’s the backer of a proposed mega-mall in Hialeah complete with an indoor water park and ice rink. Three other of the top slots are held via PACs by Daniella Levine Cava’s chief political advisor who counts three Miami-Dade Democratic commissioners as clients and whose other income comes from lobbying on behalf of developers.

‘NO AD’ subscription for CDM! Sign up here and support real investigative journalism and help save the republic!

Thirteen out of 16 donors, then, are playing the real estate game that currently promotes “densification” and mostly benefits upper-income new arrivals. They are the people running the financial interests of the Democrats who are running the County. What’s getting lost in this equation is the interest of the electorate: the working and middle class voters who this year made their conservative preferences decisively clear.

Looking closer at four Democratic donors—Ken Griffin, Michael Swerdlow, Christian Ulvert, and Atlantic Pacific—gives a sense of the range of their real estate moves, how they intersect with Miami-Dade Democratic politics, and their likely effects on Miami-Dade residents.

Ken Griffin Donates to Levine Cava and Turns Brickell into a Mini-Manhattan

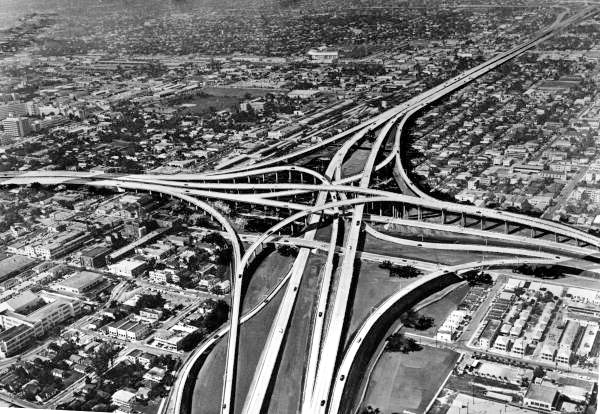

The largest donor is Ken Griffin, who recently moved his business interests from Chicago to Miami-Dade and donated $500,000 to Daniella Levine Cava’s campaign. Griffin is breaking ground on a $650 million office tower in Brickell, the city’s financial district. According to The Miami Herald, this 54-floor building will include “a 212 room hotel perched above the office floors, a 5,000-square-foot health spa and fitness club” along with “restaurants and stores” which will spill out onto the street. Landscaping is being designed by the same firm that designed Manhattan’s linear park the High Line: the first step in the remaking of Manhattan into a destination for wealthy tourists which started pushing working and middle class residents with more traditional values out of Manhattan.

Whether Griffin knows it or not, this remaking also occurred in Chicago, the city he left, with many of the same consequences that drove him away. From the 1990s to the 2010s, as your correspondent has written about elsewhere, Chicago's leaders remade it to be a "global" city: attracting capital investments and entertainment complexes and shifting the center of city power from wards to universities, churches to philanthropies. In the process, Chicago's traditional residents were displaced, creating a city of philanthropic managers and academic progressives who have encouraged Chinese infiltration, illegal immigration to keep costs low, and progressive doctrines.

The new Miami tower, according to Griffin’s spokesperson, is a leap in this eventual direction: making Miami “a global destination for talented professionals and their families, businesses and culture.” As Levine Cava’s opponent in the 2024 mayoral race, Republican Manny Cid, argued after word of Griffin’s donation to Levine-Cava broke, these are the people who are already pushing out the mostly working-and-middle-class Cuban Americans who built the city since 1959. By both redeveloping Brickell and helping re-elect Levine Cava, Griffin is supporting this pricing out not just personally but by proxy: empowering, via Levine Cava’s Democrats, powerful local players invested in unexamined growth. No one fits the bill more than Michael Swerdlow.

Swerdlow Pumps Money to Keon McGhee, Employs Christian Ulvert, and Remakes Little Haiti

Swerdlow’s donations start with Keon McGhee, the Democratic County Commissioner who represents a site in Southwest Miami-Dade which Swerdlow bought this year from the County for $8.1 million plus another $1 million over the next decade for "sewer projects and neighborhood expenses" to construct a Costco, despite the fact that the land is valued at $31 million. (“County selling 17 acres it needs to Costco at big discount,” wrote the County paper Miami Today, summing up the situation.) Mentioned in connection to this transaction was Christian Ulvert, who takes up three spots on The Miami Herald’s top donors’ list through three separate PACs. As a lobbyist, Ulvert represents Swerdlow. As a political operative, Ulvert represents Mayor Levine Cava and three Democratic Commissioners. One of these commissioners, Eileen Higgins, was up for reelection along with Keon McGhee and Mayor Levine Cava in 2024. So it may not be a coincidence that with McGhee, Levine Cava, and Ulvert receiving his funds, Swerdlow chose 2024 to make a play for a prime development in Miami: low income neighborhoods just north of the river.

In 2024, Swerdlow submitted for the County’s consideration a proposal for a 65 acre redevelopment of public and private land in Little Haiti at the projected cost of $2.6 billion; what The Miami Herald calls a “gargantuan” proposal that might be the largest in the County’s history. Tellingly, Swerdlow submitted the proposal without de facto competition (he was the only local developer to bid). He also did it in response to an extremely modest county request: privatize and refurbish two dilapidated public housing apartments of 230 units in total.

Swerdlow justifies the proposal’s unasked-for scope based off the fact that he’ll be building 5,000 apartments, which means that none of the current residents in the area will have to move. What he doesn’t answer is the question of what residents he’ll be bringing in. Though 1400 units will be reserved for very low income residents, the rest “would be affordable to people making no more than 120 percent of the county’s median household income, or a maximum of around $90,000.” When you take into account that the median income in Little Haiti is $36,329, the process becomes clear. This is not remaking a broken neighborhood for people who can live there; it’s importing new arrivals to live in a development managed by a handful of people who live far away, using federal tax credits obtained via the magic label “affordable housing.”

Though some residents are cautiously optimistic about the development without having seen details (which Swerdlow hasn’t released) Swerdlow’s track record backs up these concerns. When it comes to his recently completed $300 million “mixed income” development in nearby Overtown, The Miami Times, South Florida’s oldest newspaper serving the black community, reported that he “originally planned to offer mostly market-rate apartments.” Eventually, apparently, he “agreed to provide all 578 residential units to qualifying seniors individually earning an average of $49,560 (or 60% [Area Median Income]), a threshold that is still likely to be out of reach for many.” To put the numbers in perspective, the area median income of Overtown is, at its highest estimate, $30,000; another recent estimate is $18,300.

Atlantic Pacific Remakes Overtown with the Help of D.C.

But Swerdlow isn’t the biggest winner North of the river—at least not yet. That title goes to Atlantic Pacific, another of Miami-Dade Democrats’ top donors, which in 2024 not only donated to Levine Cava and the commissioners but also hit the ultimate real estate sweet spot: a massive development contract backed by federal money. This windfall, as your correspondent reported in December, came from HUD, which last year sent Miami-Dade a $39.9 million grant to build public housing in Overtown. It was Levine Cava ally HUD Secretary Marcia Fudge who sent the money, and it was donor Atlantic Pacific which received the contract: to redevelop “Culmer Gardens and Culmer Place, two public housing developments built in the 1970s and 1980s” by “replac[ing] the old buildings with more than 1,000 mixed-income units.”

As your correspondent noted in a past piece, “mixed-income,” like affordable housing, is a weasel word which in practice can mean either a complex built for “moderate and low-income families” or one with “a small percentage of [truly affordable units],” which are often included “to qualify for municipal subsidies.” Public comments from neighborhood residents echo this concern about the current Overtown redevelopment.

Advocates in the neighborhood have stated that, to realistically provide for Overtown’s existing communities, mixed-income housing will have to be low-income, and not just low income but 30 percent of area median income. This is because area median income for Miami-Dade developments is calculated based on Miami-Dade’s median income, which is nearly $70,000, versus the rough estimate of $30,000’s that is Overtown’s. ($30,000 is around 42 percent of $70,000, not 30 percent, but the advocates are likely choosing 30 to be safe because in some estimates Overtown’s average median income is as low as $18,300.)

The injustice here is clear with a single example. In practice an $84,000 earner could be living in an area, backed by government subsidies, whose current inhabitants earn an average of $50,000 less. This isn’t “mixed-income” housing—this is housing for newcomers.

Another issue, according to a source with deep connections to Miami real estate, has to do with the units themselves: in the name of “densification,” developers like Swerdlow and Atlantic Pacific are building up, when they could be constructing smaller units that are more like houses. Building smaller units is what happened with smaller developments like Coral Gables a century ago: developers lived in the neighborhoods they built. But in today’s Miami, where growth in working class neighborhoods is driven by a handful of distant practitioners, a few of whom are also climate advocates who along with Levine Cava preach “building up” on ecological grounds, the “go-to” solution is high-rise developments where many people don’t want to live but where, because of the housing crunch, they'll agree to live anyway.

Un-representative Politics—and the Bigger Threat to the County

None of the politics driving this growth is remotely representative; it’s transactional politics between a small number of people that sometimes seems literally rigged. After the County commissioners’ meeting to decide on Swerdlow’s purchase of the Southwest Dade site for Costco, a woman who spoke to the commissioners in favor of the purchase on behalf of local residents told The Miami Herald she had been offered money to do so. More recently, Swerdlow’s Little Haiti project, according to The Miami Herald, has, “despite its breadth…so far flown under the public’s radar” because county officials have refused to comment on it, citing “a ‘cone of silence’ rule meant to bar lobbying while proposals are vetted.” This explanation doesn’t compute. If Swerdlow has spent the year actively donating to Democratic county commissioners, the Democratic county mayor, and the mayor’s chief political operative (Christian Ulvert), has Swerdlow not been de facto lobbying while his proposal is being vetted?

The problem with this sleight-of-hand politics is that it creeps up on the electorate unawares, because its targets start small and then get bigger. Little Haiti and Overtown, which are some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods in part thanks to past Liberal-backed developments, can seem a long way from the rest of Miami-Dade. But, as your correspondent’s report on Li’l Abner’s fight against government-backed realtors has shown, displacement is the situation increasingly faced by working and even middle-class Miami-Dade residents. If something doesn’t change, if we don’t clean house of Democrat politicians, we may all soon be displaced, or living miserably in a “densified” county, together.

Ken Griffin is funding in Miami the same woke progressive politicians that caused him to leave Chicago.

He gets an “A+” for business, finance and philanthropy, and a “D” for political science!